Elvis Is in the Building

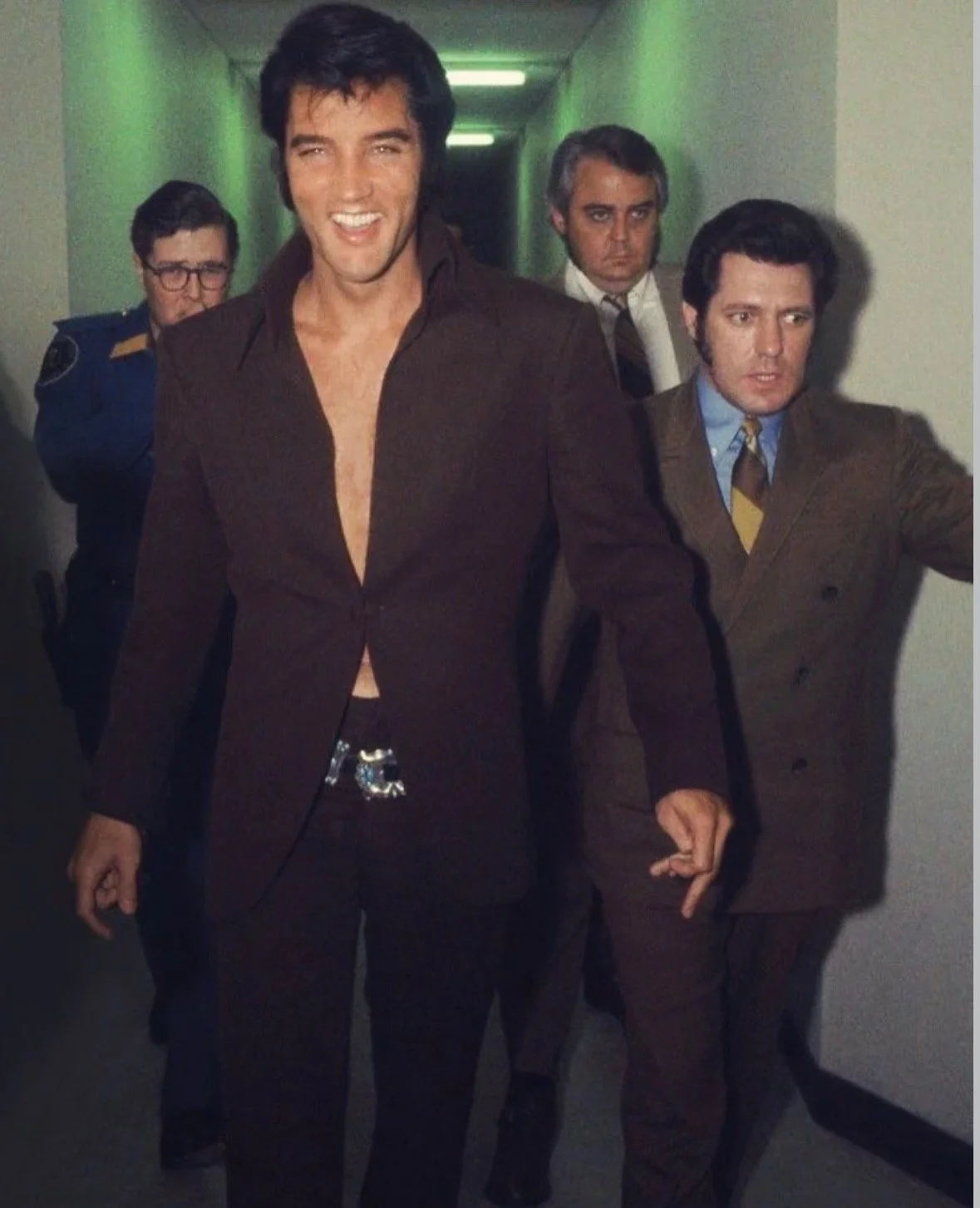

Elvis Walking in the International Hotel.

By the mid-to-late 1960s, Elvis Presley was still universally known as the King. But if you turned on the radio, it didn’t always feel true anymore. By 1967, Elvis’s singles and albums were regularly failing to reach the Top 20. It was a startling contrast to 1957, when every single he released went straight to number one. The fall wasn’t sudden, and it wasn’t accidental. It was the result of a series of choices, some strategic, some restrictive, and some simply mistimed.

One major factor was Elvis’s growing focus on acting. He genuinely wanted to be a movie star, and for a time Hollywood rewarded him for it. The problem was that the films demanded constant soundtrack material, and those soundtracks increasingly felt detached from contemporary music. Songs were written to serve scripts, not to challenge or excite listeners. Elvis the recording artist became secondary to Elvis the reliable box-office presence.

At the same time, the world around him was changing fast. The British Invasion didn’t just introduce new bands; it introduced a new idea of what an artist could be. Groups like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones wrote their own songs, toured relentlessly, and presented themselves as complete creative units. Rock music became louder, more experimental, and more personal. Elvis, meanwhile, wasn’t touring at all. To younger audiences, he began to look like a relic of an earlier era, frozen in place while the culture moved on.

The turning point came in 1968 with the NBC Comeback Special. It was Elvis’s first live performance in seven years, and it stripped away everything unnecessary. Dressed in black leather, sweating under studio lights, joking with his old bandmates, he looked dangerous again. More importantly, he sounded alive and well. The special didn’t just revive public interest; it reminded Elvis himself of what he was capable of.

The success gave him leverage for the first time in years. Shortly afterward, he drew a line in the sand, telling his producer that he would never again make a movie or record a song he didn’t believe in. In early 1969, he returned to Memphis and recorded music that felt rooted, soulful, and current. Songs like Suspicious Minds and In the Ghetto reestablished him as a serious recording artist, not just a legacy act. But Elvis still needed a stage.

Front of the International Hotel - Las Vegas 1969

Las Vegas, at the time, was undergoing its own transformation. It was no longer just a destination for lounge singers and fading stars. Residencies were becoming ambitious, high-profile events, capable of reshaping careers. Elvis saw something there. Not an ending, but a reset.

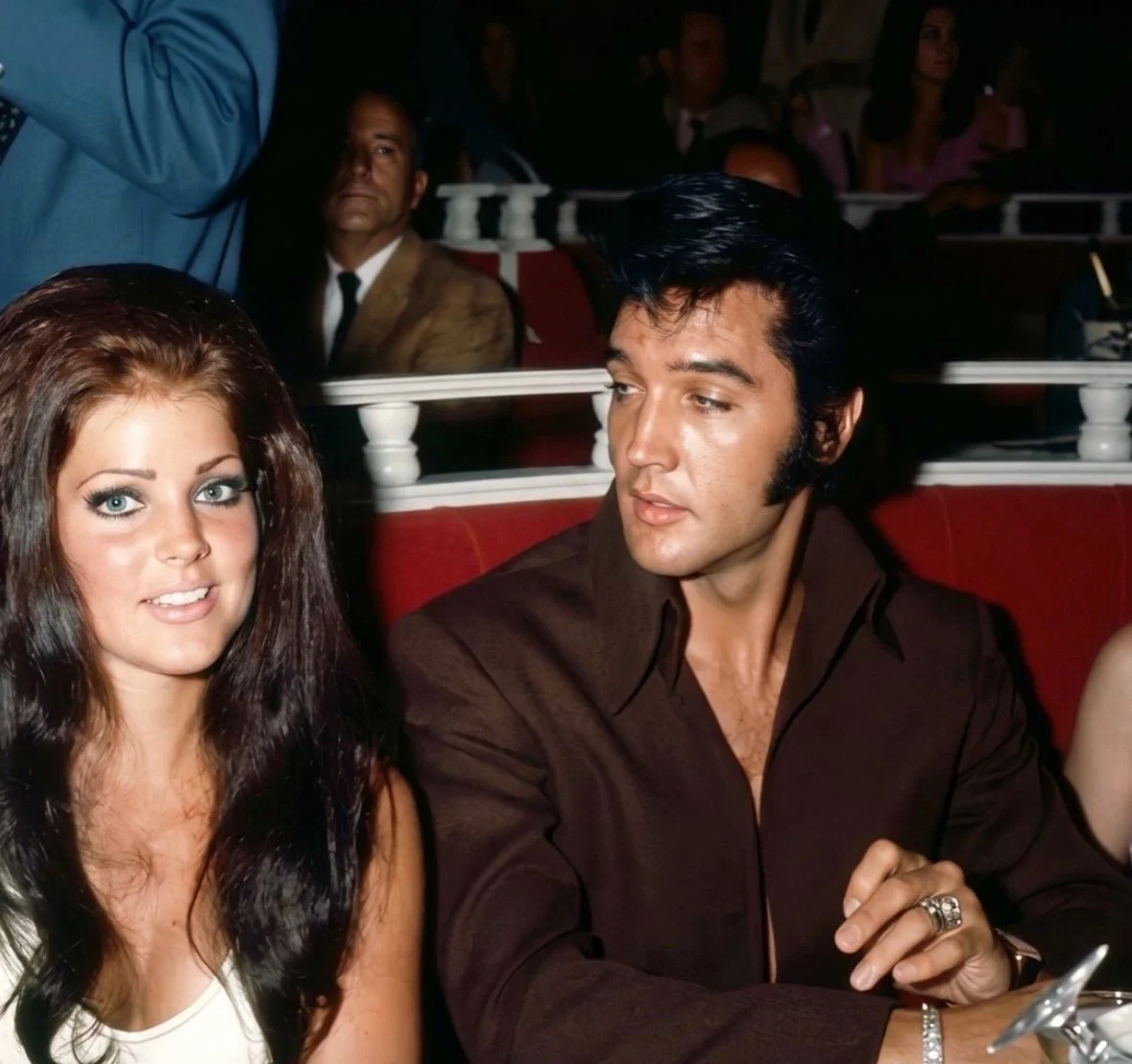

On July 28, 1969, Elvis and Priscilla Presley attended Barbra Streisand’s closing performance at the newly opened International Hotel. It was a loaded moment. Streisand was only 27 years old, fresh off an Academy Award for Funny Girl, and had just completed a record-breaking engagement that made her the highest-paid nightclub performer in history. Despite her success, she was famously terrified of returning to live performance after years away.

Elvis and Priscilla Presley attended Barbra Streisand’s closing performance at the newly opened International Hotel.

After the show, Elvis visited her backstage. Streisand later recalled being so nervous that she began painting her nails just to avoid looking him directly in the eyes. Elvis quietly took the polish from her and finished painting them himself. He was just that smooth. Three days later, Elvis opened himself at the International Hotel.

Streisand Preforming on stage at the International Hotel.

What followed erased any lingering doubts. His Vegas debut was an immediate success, and it marked the beginning of the most commercially dominant live run of his career. Night after night, the shows sold out. Over the next several years, Elvis shattered attendance records, performed hundreds of consecutive sold-out performances, and played to millions of people. The slump was offically over.

Elvis didn’t reclaim his crown by chasing trends or trying to sound young. He reclaimed it by returning to what he did best: commanding a room and being a live performer. In doing so, he didn’t just reinvent his own career; he redefined what a live residency could be.